Aphrodite Gas Lamp Globe Replacement

The front hall's Aphrodite gas (now electrified) lamp

Entering the main house’s front hall in the 1870s, you would have been met with Cornelius and Baker’s gasolier portraying Aphrodite arising from her scallop shell lighting your way. In the late 1950s, surviving thirty-five years as rooming house illumination, Aphrodite still cast her spell in the front hall, although with a different globe. By the time the house underwent a complete restoration and opened as a museum in the 1960s, Aphrodite had again a different globe.

Aphrodite's new globe, a gift from McAvoy Realty

Enter Mike McAvoy of McAvoy Realty. Ever since he moved into Lafayette Square in the 1970s, he has been exploring and studying the world of Victorian furniture and lighting. When he saw our 4-inch globe on Aphrodite, he recognized that she would have had a 2 5/8-inch fitter, the ring that supports a lamp’s glass globe, in her original configuration.

Electrified around the time of the World's Fair in 1902, she would have still carried a globe with the smaller size fitter.

Mike imagines that someone broke the globe (think errant broomstick or a carried ladder) and, because the original 2 2/5-inch globes were difficult to find, substituted a 4 inch globe and increased the size of the fitter. But the style of the latest globe was wrong for the Victorian lamp.

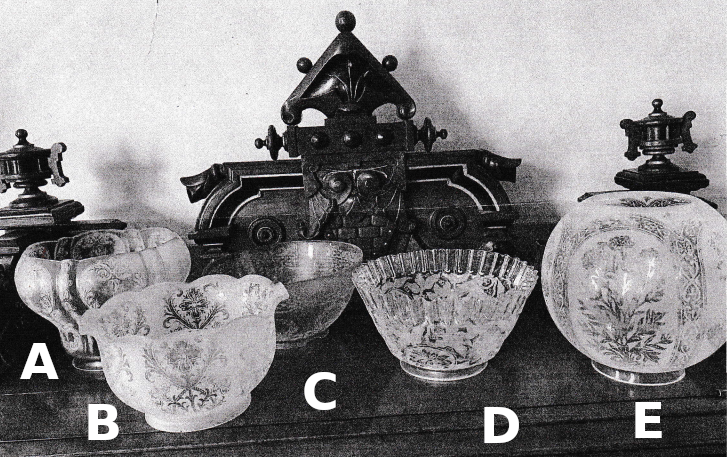

Part of Mike McAvoy's Gasolier Globe Collection

Mike researched and selected five globes from his collection and offered our House Committee a chance to pick the one most appropriate to Aphrodite in 2025, one hundred and fifty years after she first graced our house.

Lafayette, the DAR, and Our Southern Windows

On April 26th, the Olde Towne Fenton Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution hosted a special reception at the mansion honoring General Lafayette and commemorating the 100th anniversary of his 1825 tour of the United States. The event featured a captivating portrayal of General Lafayette by Michael Halbert, bringing to life the spirit of the French hero who significantly contributed to America's independence in 1776.

The DAR Committee welcomes General Lafayette

The reception beautifully highlighted the deep historical ties between the Lafayette legacy and one of St. Louis's most prominent founding families. The 1836 marriage of Sophie Chouteau to Nicolas DeMenil (1812-1882), a French-trained physician and pharmacist from Foug, France, cemented this connection. Nicolas's family boasted relations by marriage to the Lafayettes and even furnished several officers to the American fight for independence, including Baron Vio-Menil, who served as Rochambeau's lieutenant.

Sophie Chouteau DeMenil (1813-1874), a figure of "French Creole aristocracy," was a direct descendant of the very founders and earliest settlers of St. Louis. Her lineage traces back to Pierre Laclede (1729-1778) and Marie Therese Bourgeois Chouteau (1773-1814). She was the granddaughter of Pierre Chouteau (1758-1849) and the daughter of his son, Auguste Pierre Chouteau (1786-1838), an early graduate of West Point in 1806.

When General Lafayette visited St. Louis on April 29, 1825, it was Sophie’s grandfather, Pierre Chouteau, who first hosted him with a grand public "open-house" reception, followed by a dinner at his home that Sophie and her family most likely attended. Her uncle, Auguste Chouteau (1750-1829), also played a significant role in Lafayette's welcoming ceremonies.

Foundation President Mary Hayward and Michael Halbert

The family's dedication to their French heritage continued through Sophie and Nicolas's son, Alexander DeMenil (1849-1928). A proud advocate of his French ancestry throughout his life, Alexander played a crucial role in the preparations for the 100th anniversary of General Lafayette’s visit to St. Louis in 1923. For this occasion, he authored the booklet “Lafayette,” reminding Americans of the French General’s vital contribution to American liberty. Alexander also served as honorary chairman of the "Lafayette Celebration Committee" and passionately urged the adoption of President Coolidge’s suggestion that September 6th (Lafayette’s birthday) be nationally proclaimed "Lafayette Day." He famously noted that “Lafayette and Washington will live in the memory of men when Caesar and Napoleon will be forgotten.”

Subsequent to the reception, the Cornelia Green Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, generously supported the restoration of fifteen windows on the south side (Cherokee Street side) of the mansion. Kennedy Painting undertook the meticulous project, which involved:

--Carefully removing old paint without damaging the historic wood, followed by priming with a high-quality primer specifically designed for historic surfaces.

--Replacing damaged or cracked glazing, installing new glazing putty, and inserting new glass panes where needed.

--Applying multiple coats of historically accurate paint color to the window frames, sashes, and trim.

Below. before and after restoration: a sill on the west-facing Chatillon parlor window

These restoration efforts ensure that this magnificent piece of St. Louis history continues to stand as a testament to the city's rich past and its enduring connections to American and French heritage.

Notes D'actualité

-- We are working with a Cherokee neighbor, Nistenhaus Design, to increase utilization of our Carriage House and patio. Already scheduled is an early-August wedding. Already held was a mid-June proposal in the gazebo.

-- The Cherokee-Lemp special Business District, as one of its last acts before its dissolution, gave the Chatillon-DeMenil House Foundation its parking lot at 1907-1909 Cherokee Street. Credit for this generous gift goes to Shashi Palamand, a member of our Board of Directors, who engineered the transfer.

-- We have engaged Reedy Press of St. Louis to supply us with local and regional book titles for sale in our recently relocated Gift Shop in the Carriage House office area.

-- We have recently republished two articles from the January 1966 Missouri Historical Society Bulletin, Henry Chatillon, by Mrs. James O'Leary, and The Chatillon-DeMenil House, by Gerhardt Kramer. The reprint is for sale in the Gift Shop for $5.

-- We have added Guest WiFi to our ammenities available for our visitors.

-- Thanks to a generous donation from Jane Gleason, Dennis Boehle's tree service manicured the magnolia trees surrounding the patio.

-- Our recent Trivia Night, held in conjunction with Campbell and Field Houses at the IBEW Hall, was a great success, raising money for all three houses in what has become an annual Spring event.

-- We have added an additional handrail to the stairs from the 2nd floor front hallway to the 3rd floor which houses the Joseph Meisel World’s Fair Collection.

-- Mary McCartney of St. Louis generously donated to our World's Fair collections the ten volume set of Louisiana and the Fair, published in 1904, being an "exposition of the world, its people, and their achievements."

The Literature of the Louisiana Territory

by Alexander Nicolas DeMenil

and a

Shared Journey on the Mississippi

In 1902, two notable figures with strong ties to St. Louis found themselves on the same steamboat journey, though whether their paths truly intersected remains a fascinating mystery. Alex DeMenil, a prominent St. Louis literary figure and scion of a distinguished local family, was aboard a steamboat out of St. Louis. His mission? To act as a translator for French visitors, preparing for the grand 1904 World's Fair.

Also on board was none other than Mark Twain, the beloved American author, as part of one of his lecture tours across the country. A ceremony on board took place to honor him, renaming the harbor boat the Mark Twain.

Despite their shared voyage and the boat's namesake tribute, we don't know for certain if DeMenil and Twain ever met or spoke that day. However, a popular rumor suggests that Alex DeMenil held a less-than-favorable opinion of Samuel Clemens (Twain's real name), reportedly considering him a "savage" who wrote "about common people, using common language."

This rumored disdain seems to be supported by DeMenil's later writings. In an article about Samuel Clemens published two years after their time together on the Mark Twain, within his essay collection titled Literature of the Louisiana Territory, DeMenil sharply criticized Twain's work. He wrote that Twain "violated nearly all the canons of literary art," employed "themes (that) were thoroughly commonplace," was "coarse," and "unnatural and straining after effect." Perhaps the most cutting remark was DeMenil's assertion that Twain "lacks the education absolutely necessary to a great writer."

It's intriguing to consider the potential encounter, or lack thereof, between these two men and the stark contrast in their literary philosophies. While one championed the voice of the common person, the other upheld more traditional literary standards. Their shared journey on the Mississippi offers a glimpse into the diverse literary landscape of the era, and the enduring debate over what constitutes "great writing."